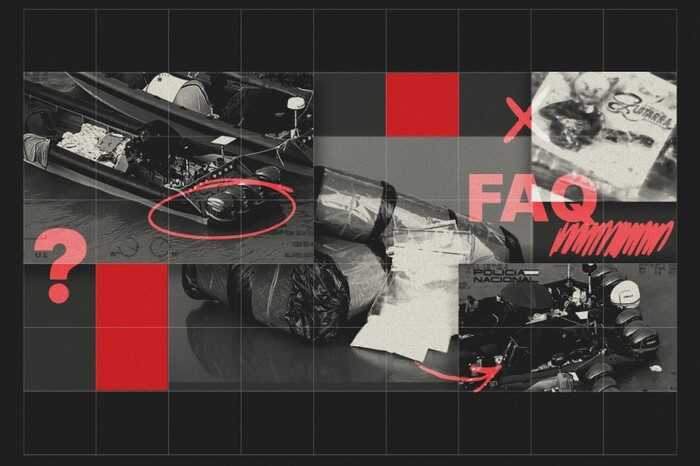

Europe Drowns in Cocaine: Oversupply, Hidden Bunkers, and “Narco-Submarines” Are Changing the Game

Wholesale prices are in the gutter across much of Europe, forcing drug smugglers to try to manipulate the market. OCCRP explains the factors affecting Europe’s cocaine supply in 2025.

On a cool cloudless morning at the break of dawn last December, authorities spotted two speed boats carrying a number of large packages at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in southwest Spain.

Civil guard officials followed the boat’s cargo as it was whizzed some 60 km upriver to a farm protected by armed guards in the town of Coria del Río, on the fringes of Seville.

During a search of the farm, the civil guard said it uncovered two shipping containers buried underground. Opening a hatch at the top, they discovered seven metric tons of cocaine, with an estimated street value of some 420 million euros.

One of the cocaine bricks fished out by the civil guard showed a devil emoji playing the guitar.

Although the cocaine bust was far from Spain’s biggest, it reveals how traffickers are adapting to a crackdown at Europe’s major ports by using alternative landing sites, and caching their wares in a market awash in cocaine.

Ballooning coca cultivation, shifting criminal networks, and the increasing use of “narco-subs” and “chemical camouflage” are among a confluence of factors that have created a massive cocaine glut in Europe.

Combined with fierce competition between traffickers, oversupply has caused the wholesale price of cocaine to collapse to all-time lows in many countries — reaching a point where some traffickers find selling is no longer profitable.

“There is greater competitiveness and more maneuverability for criminal enterprises,” said Cesar Alvarez Velasquez, a fellow at the Innovation for Development Foundation, a Colombian think tank.

“Those at the top of the pyramid have become very efficient, with a high capacity to mitigate risks, have very rapid scalability, and the ability to offer very competitive prices.”

But while users have enjoyed an incremental bump in purity, the street price of cocaine remains largely unchanged. Instead of passing on the savings to customers, trafficking networks have started hoarding vast quantities of cocaine, aiming to throttle supply and allow wholesale prices to bounce back.

Through interviews with more than a dozen top law enforcement officers and drug experts across Europe and Latin America, OCCRP has pieced together the evolving narcotics landscape to explain why some drug gangs are literally burying their “Florida snow.”

“There are huge stockpiles. You have examples in Spain where the cocaine is buried in the bunkers under the ground,” said Robert Fay, head of the drugs unit at Europol. “Everybody is asking: ‘What the hell has happened?’”

Why has cocaine production exploded?

The first part of the puzzle lies across the Atlantic Ocean in the jungles of Colombia, which is the world’s largest grower of coca, the bush from which cocaine is manufactured.

The amount of land where coca is grown in the South American nation expanded by almost two-thirds between 2018 and 2023 to 253,000 hectares, roughly the size of Luxembourg, according to the latest available data from the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Over the same period, potential production more than doubled to 3,708 metric tons, equal to the weight of around 300 double decker buses, UNODC data shows.

Accordingly, coca leaf prices fell sharply to around $5 per arroba (a Colombian imperial weight equivalent to around 12.5 kg) in 2024, down from around $18 two years earlier, Colombia’s Rural Development Agency said in a report.

The production boom boils down to three main things: failed policies, agricultural innovation in concentrated areas, and a constellation of smaller armed groups taking over, who are focused on profits over politics.

Ahead of the landmark 2016 peace deal with the country’s biggest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the government suspended aerial spraying of coca crops with a toxic herbicide.

“With less pressure, farmers no longer have to spend time and resources on replanting, but can instead invest in improving their crops, in agrochemicals, in selecting plants, and in consolidating what they already have,” said Ana María Rueda, drug policy analysis coordinator at the Colombian Ideas for Peace Foundation.

At the same time, a government crop substitution scheme proved counterproductive. Farmers who had never grown coca started to plant it so they could qualify for a subsidy that would pay them to grow an alternative crop.

Farmers also began cultivating new, high-yield strains of coca that can be harvested several times a year, significantly boosting potential output.

“[Around] 90 percent of the crops have been concentrated in the same places for a decade. This has made it possible to consolidate networks, exchange seeds, experiences, knowledge, techniques, and this impacts productivity,” Rueda said.

Candice Welsch, UNODC representative for the Andean region, told a news conference last year that twice as much coca can be produced from the same plot of land compared to a decade ago, according to reporting by Bloomberg.

Furthermore, the void left by FARC militants who once regulated the market and imposed price controls allowed other armed groups to sweep in, introducing more efficient processing techniques and a competitive market that lowered farmgate prices.

Lastly, vast stockpiles of the drug that built up during the COVID pandemic, when trafficking slowed but production continued, are fueling “a virtually inexhaustible supply” across South America, said Juliana Grotz, a spokesperson for Munich prosecutors.

Producers have lowered prices to shift merchandise in any way they can, said Alberto Morales, head of the anti-drug brigade in the Spanish police.

“If they keep the merchandise stored, only two things can happen: It gets stolen or the police seize it.”

Are authorities trying to seize all this cocaine?

Yes, and they’re succeeding. For the seventh consecutive year, EU member states seized a record amount of cocaine in 2023.

Belgium, Spain, and the Netherlands remained at the top of the seizure leaderboard in 2023, reflecting their importance as entry points for cocaine trafficked to Europe, while Spain reported its largest ever cocaine bust last year, 13 tons hidden in a shipment of bananas from Ecuador.

But it hasn’t been enough to hold back the flood.

“[Cocaine], it’s like water. It finds its way,” said Martin Van Nes, the national prosecutor for cocaine trafficking in the Netherlands.

Despite record-breaking efforts by authorities in recent years, only a fraction of the smuggled cocaine is ever captured.

“In Spain, 80 percent of cocaine is seized in containers. And 10 percent of containers are inspected. So do the math,” said a senior anti-drug officer in Catalonia.

The bulk of cocaine arriving on Europe’s shores comes directly by sea, concealed in the millions of shipping containers that pass through the continent’s major ports every year, but that’s starting to change.

Aided by the cracking of two encrypted messaging platforms, Sky ECC and Encrochat, stricter border controls and inspections at major ports, European officials seized a record 419 metric tons of cocaine in 2023, according to EUDA, roughly the weight of a fully loaded Boeing 747.

But the success was short-lived. The following year, seizures at the ports in Antwerp and Rotterdam cratered, even as cocaine usage continued to climb, as revealed by increased cocaine residue in waste water across major European cities.

“Hacking of these communication platforms created a disruption in the traffic. So the network had to adapt,” said Fay from Europol.

What new routes are being used by cocaine smugglers?

Improved interdiction at large ports has forced traffickers to find innovative ways of evading detection, such as using different transit points, smaller ports, semi-submerged vessels known as “narco-subs,” transfers of cargo at sea, planes, and chemical concealment.

West Africa has grown from a transit point into a logistics hub as corruption and lackluster policing in countries like Sierra Leone, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, and Cabo Verde allow the origins of a shipment to be obscured, making cocaine harder to track and seize when it makes landfall in the EU.

Law enforcement told the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime that they believe almost one third of Europe’s cocaine is now routed through West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea, and they expect that to rise to half by 2030.

“There are structural factors that keep West Africa attractive in the long term,” said Kars de Bruijne, head of the Sahel program at Clingendael Institute, a Dutch think tank.

These are “significantly improving infrastructure and connections to global markets, and political structures that make it easier for global organized crime to be protected,” de Bruijne said.

Shipments are then being diverted to landing sites in Europe that are less well monitored, European officials say.

“Organizations aren’t stupid. If you’re hitting a port all day, they’ll move to another one,” said Morales from the Spanish police.

“Colombians call it the balloon effect, you know. You press one side and then it goes to another.”

A significant cut of the traffic is now going through the old hashish smuggling routes from Morocco, or being collected from fishing boats and narco-subs far from land in the Atlantic Ocean, Morales said.

“Narcos drop the cocaine in the sea, and it is recovered there by speedboats that then go up the Guadalquivir River, and drop the cocaine on the banks,” Morales said.

Who are the new players in cocaine smuggling?

One of the most significant changes to the way cocaine trafficking networks operate in recent years has been fragmentation and decentralization of the supply chain, which has streamlined processes and reduced costs.

“It is no longer the cartel that controls the chain from A to Z, but several groups specializing in a specific stage of supply,” said Yasmine Salhi, an economist at the French Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. “So they are really professionalized for one task.”

They tend to work in small cells that form alliances with each other, rather than in classic hierarchical criminal organizations, said Fatjona Mejdini, a Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime researcher.

“As a result, cells operating, for example, in Latin America, that nobody had heard of before have turned out to be quite powerful,” Mejdini said.

Several of the groups with an increased foothold across the trade are Albanian and Slavic-speaking gangs from the Western Balkans.

They not only buy directly from groups in South America, particularly Ecuador, but have expanded multi-tonne transhipments via Brazil and West Africa, according to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

Brazil doesn’t grow coca, but an arrangement between its biggest organized crime syndicate, Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), and mafia organizations like Italy’s ’Ndrangheta and Western Balkan groups such as the Kavač and Škaljari clans from Montenegro, now underpins a significant proportion of Europe-bound cocaine flows, according to a Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime report.

PCC trafficks the drug through Brazil and offers its logistics and network of contacts to others, like a trusted broker between growers and traffickers, ensuring neither side gets ripped off, said Gabriel Feltran, a professor at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po).

“The PCC functions as a platform, in the same sense as Uber or Airbnb… in a business structure that allows many independent entrepreneurs to connect,” Feltran said.

How is cocaine being concealed?

Authorities suspect that more sophisticated concealment could also explain the decline in busts at major ports.

“They are looking for why, and they don’t know,” said Laurent Laniel, an analyst at EUDA. “There are hypotheses; one of them is chemical camouflage.”

While the predominant mode of trafficking still involves transporting finished cocaine in kilogram-sized bricks, traffickers also use a variety of concealment techniques to avoid detection, according to a 2024 United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) report.

Physical camouflage involves washing the cocaine base, a partially processed extract, into clothes or cardboard, or mixing it with substances like coffee, fertilizer, or coal, the DEA said.

One indicator supporting this hypothesis is the discovery of more cocaine laboratories across Europe in the last few years, said Janneke Hulshof, a narcotics specialist at the Netherlands Forensic Institute.

In these laboratories, the concealed drug is extracted from its carrier material using chemicals such as caustic soda, hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, and different solvents.

Chemical camouflage, where the cocaine has been altered at the molecular level, is even harder to detect, because it can be hidden in plastics or metals. Normal tests, which turn blue if cocaine is present, won’t register it.

“That blue color simply doesn’t come out,” Hulshof said. “It’s no longer recognized as cocaine.”

The Iberian Peninsula, but also other countries like Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany, show a slight increase in busts of laboratories extracting or reprocessing cocaine, or both, said Fay from Europol.

Colombian drug experts have told Europol they believe around 20 percent of cocaine shipped to Europe from Colombia is now being smuggled by chemical camouflage, Fay said.

“Never before has organized crime had so much venture capital available to invest in corruption… [and] better concealment methods,” said Daniel Brombacher, who leads the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime’s work in Europe.

What effect is all this having on cocaine prices?

Prices vary widely across Europe, but authorities in several countries said the wholesale price of cocaine had roughly halved in the last year, while retail prices have remained relatively unchanged.

The economics of illicit drug markets don’t always function like those of legal goods. Experts say falling wholesale prices have nudged up the purity of cocaine sold on the street, but not affected prices.

Drug prices are regulated to a degree by cutting, said Ramon Chacón, head of criminal investigation in the Catalonian police, referring to the purity of a drug.

With cocaine, the street price is overwhelmingly determined by the dealers’ perceived risk of arrest or violence rather than the wholesale cost, UNODC research shows.

A little over a year ago, a 1-kg block of cocaine cost close to 30,000 euros in the Netherlands, said Dutch prosecutor Van Nes. According to his sources, it’s now closer to 15,000 euros, Van Nes said. Officials in Spain and Germany, and at Europol, report similar prices.

"One of our informants told us that traffickers are saying: ‘I won’t traffic for less than 12,000 euros per kg because the numbers don’t add up for me,’” Spanish anti-drug police chief Morales said.

In response, traffickers are hoarding the merchandise to force the price back up, Morales said.

In Coria del Río, the local administration’s website invites potential visitors to discover “our unique history, welcoming people, and rich cuisine, and to join us in enjoying the beautiful landscapes on the banks of the Guadalquivir.”

It doesn’t mention that its riverside location also makes it a convenient spot to unload and stash bundles of cocaine while you wait for wholesale prices to bounce back.

Читайте по теме:

Комментарии:

comments powered by Disqus 04.11.2025, 20:39 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 20:39 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 20:30 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 20:30 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 20:27 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 20:27 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 20:21 • Дайджест

04.11.2025, 20:21 • Дайджест

04.11.2025, 20:09 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 20:09 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 20:03 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 20:03 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 20:00 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 20:00 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 19:51 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 19:51 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 19:33 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 19:33 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 19:06 • Криминал

04.11.2025, 19:06 • Криминал

04.11.2025, 18:30 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 18:30 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 18:06 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 18:06 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 17:51 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 17:51 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 17:39 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 17:39 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 17:24 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 17:24 • Конфликты

04.11.2025, 17:03 • Открытия

04.11.2025, 17:03 • Открытия